“I know that architecture is life; or at least it is life itself taking form and therefore it is the truest record of life as it was lived in the world yesterday, as it is lived today or ever will be lived.”— Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959)

Frank Lloyd Wright was born during the historic transition from the horse-drawn nineteenth-century to the industrial and mechanical twentieth-century. Wright enthusiastically welcomed the social and technological changes made possible by the Industrial Revolution. His primary goal was to create a new architectural movement that addressed the individual physical, social, and spiritual needs of the modern American citizen.

To Wright, architecture was not just about buildings, it was about nourishing the lives of those sheltered within them. He called his architecture “organic” and described it as that “great living creative spirit which from generation to generation, from age to age, proceeds, persists, creates, according to the nature of man and his circumstances as they both change.”

Wright’s greatest muse was Nature, which he spelled with a capital “N.” He explained this notion as follows:

“Using this word Nature…I do not of course mean that outward aspect which strikes the eye as a visual image of a scene strikes the ground glass of a camera, but that inner harmony which penetrates the outward form…and is its determining character; that quality in the thing that is its significance and it’s Life for us,–what Plato called (with reason, we see, psychological if not metaphysical) the “eternal idea of the thing.”

In 1991 the American Institute of Architects named Frank Lloyd Wright the greatest American architect of all time, and Architectural Record included twelve of Wright’s structures in a list of the one hundred most important buildings of the previous century. Twenty-five Wright projects have been designated National Historic Landmarks, and ten have been named to the tentative World Heritage Site list.

His Usonian homes, which were built starting in the late 1930s, were intended to be highly practical houses for middle-class clients, and designed to be run without servants. Usonian houses often featured small kitchens — called “workspaces” by Wright — that adjoined the dining spaces. These spaces in turn flowed into the main living areas, which also were characteristically outfitted with built-in seating and tables. As in the Prairie Houses, Usonian living areas focused on the fireplace. Bedrooms were typically isolated and relatively small, encouraging the family to gather in the main living areas. The conception of spaces instead of rooms was a development of the Prairie ideal; as the built-in furnishings related to the Arts and Crafts principles from which Wright’s early works grew. Spatially and in terms of their construction, the Usonian houses represented a new model for independent living, and allowed dozens of clients to live in a Wright-designed house at relatively low cost. Wright identified the challenge of building “the house of moderate cost” as “not only America’s major architectural problem, but the problem most difficult to her major architects. I would rather solve it with satisfaction to myself than anything I can think of.”

These projects led to the Erdman homes, a series of three prefabricated structures that Wright designed for Marshall Erdman, a builder who had collaborated with Wright. The prefab package Erdman offered included all the major structural components, interior and exterior walls, floors, windows and doors, as well as cabinets and woodwork. In addition to a lot, the buyer had to provide the foundation, the plumbing fixtures, heating units, electric wiring, and drywall, plus the paint. Before the prospective buyer could purchase the house, they needed to submit a topographic map and photos to Wright, who would then determine where the home should sit on the lot. Wright also intended to inspect each home after completion, and to apply his famous glazed red signature brick to the home if it had been completed as planned.

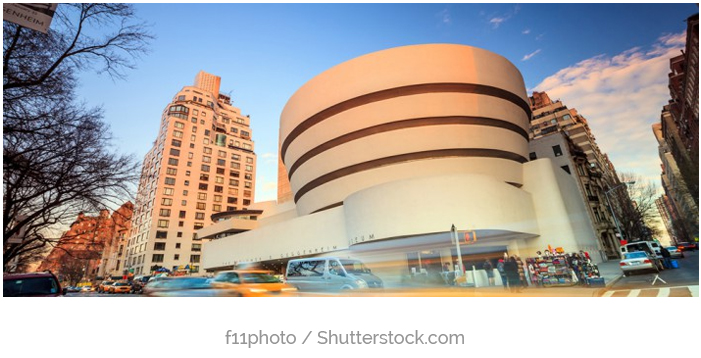

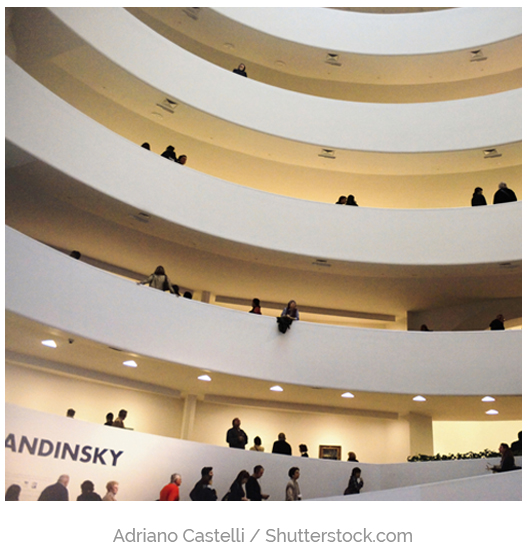

During his career, Wright designed over 1000 buildings. One of Wright’s most iconic designs is the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. It took him 16 years to complete. The building rises as a warm beige spiral from its site on Fifth Avenue; its interior is similar to the inside of a seashell. Its unique central geometry was meant to allow visitors to easily experience Guggenheim’s collection of non-objective geometric paintings by taking an elevator to the top level and then viewing artworks by walking down the slowly descending, central spiral ramp, the floor of which is embedded with circular shapes and triangular light fixtures to complement the geometric nature of the structure.

Just a few of the major milestones in Wright’s life:

1885 – Wright takes a part-time job as a draftsman.

1889-1892 – Wright works at the architectural firm of Adler and Sullivan.

1890 – Wright is assigned all residential design handled by Adler and Sullivan.

1893 – Wright opens his own practice.

1900 – He writes the lecture “A Philosophy of Fine Art” and “What is Architecture?” as well as articles on Japanese prints and the culture of Japan.

1926 – Wright starts work on his autobiography.

1927 – Wright is made an honorary member of the Academie Royale des Beaux Arts, Belgium.

1938 – Wright designs the January issue of Architectural Forum, which is dedicated to his work. Wright appears on the cover of Time Magazine.

1947 – Wright is awarded an honorary doctorate of fine arts by Princeton University.

1956 – Wright publishes his final book, The Story of the Tower.